New York City. The packed 3 train screeches to a stop at Times Square. I disembark, and on the platform, a sea of people bottlenecks at the base of the escalator. Above ground, I am a speck in a skyscraper valley of illuminated advertisements. Cars honk, not to solve anything, but to communicate frustration. I dodge distracted bodies moving toward me, weave through the slow pedestrians. Within five minutes on my journey, I receive offers of: drugs, last-minute Broadway tickets, more drugs, and a bottle of water. Someone asks me for money. Blue lights flash, and a man is handcuffed across the street. A performer in a bulky SpongeBob SquarePants costume dances at the corner.

It can be difficult to discern what stimuli to let in, and which to shut out. What to feel, what to numb myself to. To live in this city is to immerse myself in the highest heights of the technological sublime, which can feel intoxicating. It is also to witness up close many contrasting facets of human experience, including suffering and injustice so plainly visible at every turn, which can feel destabilizing.

Call it the Anthropocene, late-stage capitalism, the deterioration of social fabric at every level, the promises and dangers of soon-to-emerge artificial general intelligence. The world, to me, can feel cacophonous. Noisy with appeals to my exasperation. It can feel righteous to engage in the spirals, even when they disenchant everything. What passes for oppositional thinking might in fact be a further entrenchment into the terms of urgency, stuck-ness, and distrust that I would like to resist.

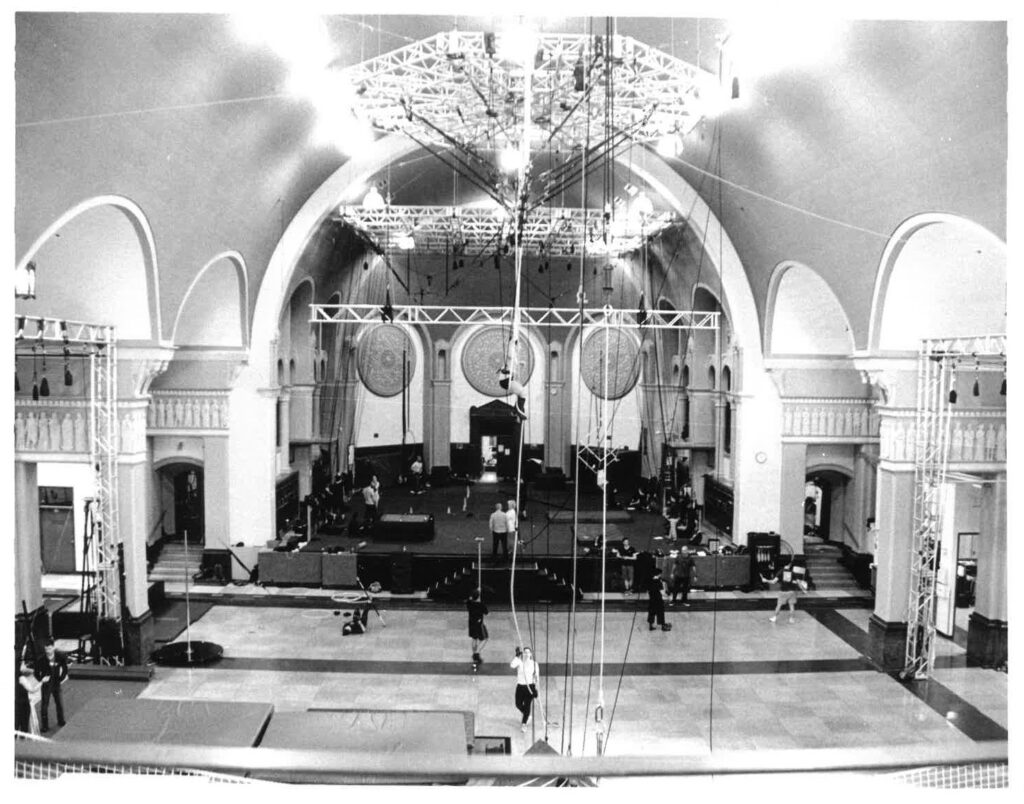

I have come to this iconic, tourist-oriented part of the city to train on aerial rope at a circus studio nearby. I do this several times each week.